- Home

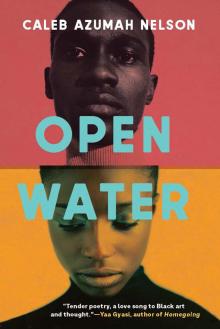

- Caleb Azumah Nelson

Open Water

Open Water Read online

Praise for Open Water

“Caleb Azumah Nelson explores the power of being truly seen by another, in a world that often refuses to recognize you at all. An exhilarating new voice in British fiction.”—Vogue (UK)

“A poetic novel about Black identity and first love in the capital from one of Britain’s most exciting young voices.”

—Harper’s Bazaar

“This shattering love story about two Black British artists is a compelling insight into race and masculinity. You’ll remember this author’s name.”—Elle (UK)

“Achingly tender and intensely moving . . . a majestic debut.”

—Cosmopolitan (UK)

“For those that are missing the tentative depiction of love in Normal People, Caleb Azumah Nelson’s Open Water is set to become one of 2021’s unmissable books . . . an exploration of desire, love, trauma, race and art. Utterly transporting, it’ll leave you weeping and in awe.”—Stylist (UK)

“Set to the rhythms of jazz and hip hop, Open Water is an unforgettable story about making art and making a home in another person. In language bursting with grief and joy, Caleb Azumah Nelson has written the ode to Black creativity, love, and survival that we need right now.”

—Nadia Owusu, author of Aftershocks

“Open Water is tender poetry, a love song to Black art and thought, an exploration of intimacy and vulnerability between two young artists learning to be soft with each other in a world that hardens against Black people.”

—Yaa Gyasi, author of Homegoing

“Like the title suggests, Open Water pulls you in with one great swell, and it holds you there closely. A beautiful and powerful novel about the true and sometimes painful depths of love.”

—Candice Carty-Williams, author of Queenie

“Open Water is a beautifully, delicately written novel about love, for self and others, about being seen, about vulnerability and mental health. Sentence by sentence, it oozes longing and grace. Caleb is a star in the making.”

—Nikesh Shukla, editor of The Good Immigrant

“An amazing debut novel. It’s a beautifully narrated, intelligently crafted piece of love that goes deep, and then goes deeper. Let’s hear it for Caleb Azumah Nelson, also known as the future.”—Benjamin Zephaniah, author of

The Life and Rhymes Of Benjamin Zephaniah

“I fell in love at the first line. Open Water is poetry, dance and music, and art, and reading it feels like moving within love, and its iterations through all the above. The book moved me and stilled me, such sumptuous prose, that clarifies whilst also keeping reverence of the sometimes unexplainable facets of love and life and Blackness. I will always remember it, and I will always return to this novel.”

—Bolu Babalola, author of Love in Color

“Open Water is about defiance, mourning, art and music. It is an ode to being a full human being in a society that does not see you that way. It is about clinging to love in a world heavy with injustice and violence. There is not a wasted page.”

—Rowan Hisayo Buchanan, author of Harmless Like You

“A very touching and heartfelt book, passionately written, that brings London to life in a painterly, emotive way. I love its musical richness and espousal of the power of the arts.”

—Diana Evans, author of Ordinary People

Black Cat

New York

Copyright © 2021 by Caleb Azumah Nelson

Cover design by gray318

Cover photographs: (top) © Campbell Addy.

Represented by CLM Agency; (bottom)

© Regan Cameron / Art + Commerce.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or [email protected].

First published in 2021 in the United Kingdom by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House UK

Printed in the United States of America

Published simultaneously in Canada

First Grove Atlantic paperback edition: April 2021

ISBN 978-0-8021-5794-2

eISBN 978-0-8021-5795-9

Set in 11/13 pt Dante MT Std

Typeset by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available for this title.

Black Cat

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

For Es

There was an inevitability about their road towards one another which encouraged meandering along the route.

Zadie Smith

PROLOGUE

The barbershop was strangely quiet. Only the dull buzz of clippers shearing soft scalps. That was before the barber caught you watching her reflection in the mirror as he cut her hair, and saw something in her eyes too. He paused and turned towards you, his dreads like thick beautiful roots dancing with excitement as he spoke:

‘You two are in something. I don’t know what it is, but you guys are in something. Some people call it a relationship, some call it friendship, some call it love, but you two, you two are in something.’

You gazed at each other then with the same open-eyed wonder that keeps startling you at various intervals since you met. The two of you, like headphone wires tangling, caught up in this something. A happy accident. A messy miracle.

You lost her gaze for a moment and your breath quickened, as when a dropped call across a distance gains unexpected gravity. You would soon learn that love made you worry, but it also made you beautiful. Love made you Black, as in, you were most coloured when in her presence. It was not a cause for concern; one must rejoice! You could be yourselves.

Later, walking in the dark, you were overcome. You told her not to look at you because when your gazes meet you cannot help but be honest. Remember Baldwin’s words? I just want to be an honest man and a good writer. Hmm. Honest man. You’re being honest, here, now.

You came here to speak of what it means to love your best friend. Ask: if flexing is being able to say the most in the fewest number of words, is there a greater flex than love? Nowhere to hide, nowhere to go. A direct gaze.

The gaze requires no words at all; it is an honest meeting.

You came here to speak of shame and its relation to desire. There should be no shame in openly saying, I want this. There should be no shame in not knowing what one wants.

You came here to ask her if she remembers how urgent that kiss was. Twisted in her covers in the darkness. No words at all. An honest meeting. You saw nothing but her familiar shape. You listened to her gentle, measured breaths and understood what you wanted.

It is a strange thing, to desire your best friend; two pairs of hands wandering past boundaries, asking forgiveness rather than permission: ‘Is this OK?’ coming a fraction after the motion.

Sometimes, you cry in the dark.

1

/>

The first night you met, a night you both negate as too brief an encounter, you pull your friend Samuel to the side. There’s a bunch of you in the basement of this south-east London pub. A birthday celebration. Most on their way to drunk, or jolly, depending on which they’d prefer.

‘What’s up?’

‘I don’t normally do this.’

‘Usually means this is something you’ve done before.’

‘No, promise. Pinky promise,’ you say. ‘But I need you to introduce me to your friend.’

You’d like to say that in this moment, the older gentleman spinning records had faded something fast, something like Curtis Mayfield’s ‘Move On Up’, into something equally so. You’d like to say it was the Isley Brothers, ‘Fight the Power’, playing when you expressed a desire you did not wholly understand, but knew you must act upon. You’d like to say, behind you, the dance floor heaved and the young moved like it was the eighties, where to move in this way was but one of a few freedoms afforded to those who came before. And since you’re remembering this, the liberty is yours. But you did promise to be honest. The reality was you were so taken aback by the presence of this woman that you first reached to shake her hand, before opening up for the usual wide embrace, the result an awkward flapping of your arms.

‘Hi,’ you say.

‘Hello.’

She smiles a little. You don’t know what to say. You want to fill the gap but nothing comes. You stand, watching each other, in a silence that does not feel uncomfortable. You imagine the look on her face is mirroring yours, one of curiosity.

‘You’re both artists,’ Samuel says, a helpful interruption. ‘She’s a very talented dancer.’ The woman shakes her head. ‘And you?’ she says. ‘What do you do?’

‘He’s a photographer.’

‘A photographer?’ the woman repeats.

‘I take pictures, sometimes.’

‘Sounds like you’re a photographer.’

‘Sometimes, sometimes.’

‘Coy.’ Shy, you think. You leap across the conversation and watch as she darts after you. A red light leans across her face, and you catch a glimpse of something, something like kindness in her open features, her eyes watching your hands talk. It’s a familiar tongue you note, definitely south of the river. Definitely somewhere you’d be more likely to call home. In this way there are things which you both know and speak with your very being, but here go unsaid.

‘Do you want a drink? Can I get you a drink?’ You turn, noticing Samuel for the first time since the conversation started. He’s receded, slumped a little; he’s smiling, but his body betrays he’s feeling shut out. Feeling the sting of guilt, you try to welcome him back in.

‘Do you guys want drinks?’

The woman’s face splits open with genuine, kind amusement and, as it does so, there’s a hand on your elbow. You’re being pulled away; you’re needed. The dance floor has cleared a little and there is a silence filled with all that is yet to come. There’s cake and candles and an attempted harmony during ‘Happy Birthday’. You slide your camera from where it swings on your shoulder, training your lens on the birthday girl, Nina, as she makes a wish, the solitary candle on her cake like a tiny sunshine. When the crowd begins to disperse, you are tugged in every direction. As the solo cameraman, it is your duty to document.

The music starts up once more. People stand in small bunches, pausing as you focus in on kind faces looming in the darkness. The older gentleman spinning records continues on at pace. Idris Muhammad’s ‘Could Heaven Ever Be Like This’ fits.

Emerging from the crowd, you stand at the bar and crane your long neck in several directions. It is here, when you seek the woman once more, on the night in question, a night you both negate as too brief an encounter, you realize she is gone.

2

These are winter months. A warm winter – the night you met her, you misjudged the distance from the station to the pub and, having walked half an hour wearing only the shirt on your back, arrived self-conscious of the sweat on your forehead – but a winter nonetheless. It is the wrong season to have a crush. Meeting someone on a summer’s evening is like giving a dead flame new life. You are more likely to wander outside with this person for a reprieve from whatever sweatbox you are being housed in. You might find yourself accepting the offer of a cigarette, your eyes narrowing as the nicotine tickles your brain and you exhale into the stiff heat of a London night. You might look towards the sky and realize the blue doesn’t quite deepen during these months. In winter, you are content to scoop your ashes away and head home.

You mention the woman to your younger brother, who had been at the party too, building him an image from what you remember of the evening, like weaving together melodic samples to make a new song.

‘But wait – I didn’t see her?’

‘She was tall. Kinda tall.’

‘OK.’

‘Wearing all black. Braids under a beret. Real cool.’

‘Yeah, I’m getting nothing.’

‘The bar looks like this.’ You form an L-shape with your arms. ‘I’m standing here,’ you say, indicating the crook of the L.

‘Hold on.’

‘Yes?’ you say, exasperated.

‘Will it help or hinder if I tell you I was steaming that evening and remember nothing, full stop?’

‘You’re useless.’

‘No, I’m just drunk. A lot. So what happens next?’

‘What do you mean?’

You’re both sitting in your living room, nursing cups of tea. The needle on the record player scratches softly at the plastic at the end of the vinyl, the rhythmic bump, bump, bump a meditative pulse.

‘You meet the love of your life –’

‘I didn’t say that.’

‘ “I was at this party and I felt this, this presence, and when I looked over, there was this girl, no, this woman, who just took my breath away.” ’

‘Go away,’ you say, flopping back onto the sofa.

‘What if you never see her again?’

‘Then I’ll take a vow of celibacy and live in the mountains for the rest of my life. And the next.’

‘Dramatic.’

‘What would you do?’

He shrugs, and stands to flip the record. A firmer scratch, like nail against skin.

‘There’s something else,’ you say.

‘What?’

You gaze at the ceiling. ‘She’s seeing Samuel. He intro’d us.’

‘Huh?’

‘I only found out after we’d spoken. I don’t think they’ve been together long.’

‘Is that a definite thing?’

‘I mean, I think so, yeah. I saw them kissing in the corner of the bar.’

Freddie laughs and raises his hands.

‘Yeah, I’m not judging you, man. Nothing is straightforward. But yeah, you might wanna –’ He mimes scissors with his fingers.

How does one shake off desire? To give it a voice is to sow a seed, knowing that somehow, someway, it will grow. It is to admit and submit to something which is on the outer limits of your understanding.

But even if this seed grows, even if the body lives, breathes, flourishes, there is no guarantee of reciprocation. Or that you’ll ever see them again. Hence, the campaign for summer crushes. Even if you leave each other on an unending night, even if you find your paths splitting ways, even if you find yourself falling asleep alone with but the memory of intimacy, it will be a shaft of summer creeping through the gap in your curtains. It will be a tomorrow in which the day will be long and the night equally so. It will be another sweatbox, or a barbecue with little food and more to drink. It will be another stranger grinning at you in the darkness, or looking at you across the garden. Touching your arm as you both laugh too hard at a drunken joke. Breathlessly falling

through the door, gripping onto folds of flesh, or silently trying to locate the toilet in a home which isn’t your own. In the winter, more times, you don’t make it out of the house.

Besides, sometimes, to resolve desire, it’s better to let the thing bloom. To feel this thing, to let it catch you unaware, to hold onto the ache. What is better than believing you are heading towards love?

3

You lost your grandma during the summer you were sure you could lose no more. You knew before you knew. It wasn’t thunder’s distant rumbling like a hungry stomach. It wasn’t the sky so grey you were worried the light would not shine again. It wasn’t the strain in your mother’s voice, asking you not to leave home before she got there. You just knew.

You return to a memory of a different time. Sitting behind the compound in Ghana, where embers of heat so late in the day make you sweat. As your grandma sits on a rickety wooden stool, chopping ingredients for a meal to be prepared, you’ll tell her that you met a stranger in a bar, and you knew before you knew. She will smile, and laugh to herself, keeping her amusement contained, encouraging you to go on. You’ll tell her how this woman was slight, but tall, carried herself well, not in a way as to intentionally intimidate or placate, but in a way that implied sureness. She had kindness on her features and didn’t mind when you hugged her.

What else? your grandma will ask.

Hmm. You’ll tell her that when you and the stranger introduced yourselves, you both played down the things you did, the things you loved. Your grandma will pause at this detail. Why? she’ll ask. You don’t know. Perhaps it was because you had both lost that year, and though you kept telling yourself you couldn’t lose any more, it continued to happen.

So? There’s no solace in the shade, your grandma will say.

I know, I know. I think both of us kinda negate that whole encounter. It was too brief. There was too much going on. It wasn’t the right time.

Your grandma will put down the knife, and say, It’s never the right time.

Open Water

Open Water